HAROLD (HARRY) HODGES

Pioneer builder in St John’s Wood

Harold was born in 1909 in Abercynon, a small village in south Wales to parents George Henry Hodges and his wife Ada. Harold’s sister Dorothy, (my mother) was three when he was born.

The children didn’t know their father for long. He was killed in an accident in the Dowlais coal mine in 1912. Ada was pregnant with their little brother Edgar. It was to be a life of poverty and hardship ahead for Harold and his family, but perhaps eased somewhat for Harold as he was his mother’s favourite. Ada had TB and was in poor health. The children spent several years in local orphanages while she was having medical treatment.

During World War 1, Ada met and eventually married, an Australian Scottish soldier, Charles Ballardie. He brought the family to Australia in 1919 and took them to Blackall, where life was primitive and conditions harsh, especially for Ada. Harold was ten and had two years of schooling at Blackall, with brother Ed. Then the family moved north and he finished school, at age 14, in Cairns. They soon moved south due to Ada’s illness.

Mother Ada lived just seven years in Australia before she died aged 50, after six months in the General Hospital in Brisbane. Harold was now 16 and felt responsible for his sister and young Edgar, now 13. Their step father had gone his own way. Harold needed to find £1 a week to pay for the three siblings to live in a Leichhardt Street boarding house. Fortunately, the lady of the house found Harold was quite talented with making things after he made her a meat safe. She accepted his handyman labour in lieu of some of their board. During the depression he worked at a Mapleton dairy farm and made many orange cases as an extra.

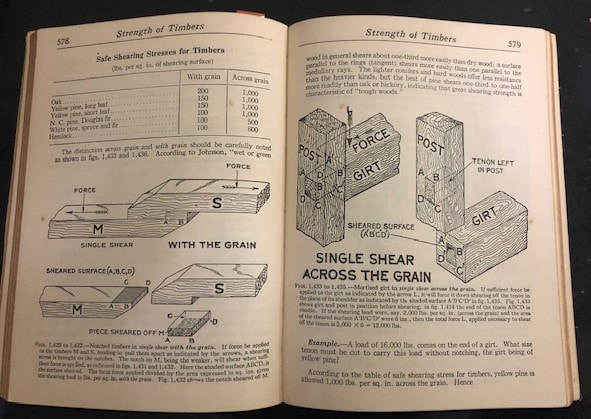

Harold found a job as an “improver”, (like an apprentice to a builder) while completing a building course by correspondence from England. He purchased four leather-bound text books, Audel’s Carpenters and Builders Guide and had them shipped out to Australia. They had thin paper pages with gold edges like a Bible. They were very comprehensive. He read these manuals thoroughly and continued to consult them over his lifetime as a builder. His son Geoff became a builder and used these same books, which, he says, equipped him with more knowledge than the average builder of his era.

The children didn’t know their father for long. He was killed in an accident in the Dowlais coal mine in 1912. Ada was pregnant with their little brother Edgar. It was to be a life of poverty and hardship ahead for Harold and his family, but perhaps eased somewhat for Harold as he was his mother’s favourite. Ada had TB and was in poor health. The children spent several years in local orphanages while she was having medical treatment.

During World War 1, Ada met and eventually married, an Australian Scottish soldier, Charles Ballardie. He brought the family to Australia in 1919 and took them to Blackall, where life was primitive and conditions harsh, especially for Ada. Harold was ten and had two years of schooling at Blackall, with brother Ed. Then the family moved north and he finished school, at age 14, in Cairns. They soon moved south due to Ada’s illness.

Mother Ada lived just seven years in Australia before she died aged 50, after six months in the General Hospital in Brisbane. Harold was now 16 and felt responsible for his sister and young Edgar, now 13. Their step father had gone his own way. Harold needed to find £1 a week to pay for the three siblings to live in a Leichhardt Street boarding house. Fortunately, the lady of the house found Harold was quite talented with making things after he made her a meat safe. She accepted his handyman labour in lieu of some of their board. During the depression he worked at a Mapleton dairy farm and made many orange cases as an extra.

Harold found a job as an “improver”, (like an apprentice to a builder) while completing a building course by correspondence from England. He purchased four leather-bound text books, Audel’s Carpenters and Builders Guide and had them shipped out to Australia. They had thin paper pages with gold edges like a Bible. They were very comprehensive. He read these manuals thoroughly and continued to consult them over his lifetime as a builder. His son Geoff became a builder and used these same books, which, he says, equipped him with more knowledge than the average builder of his era.

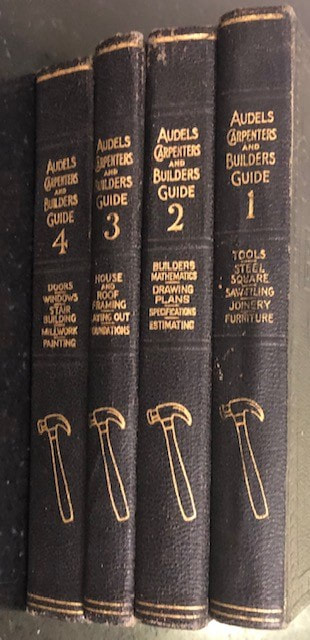

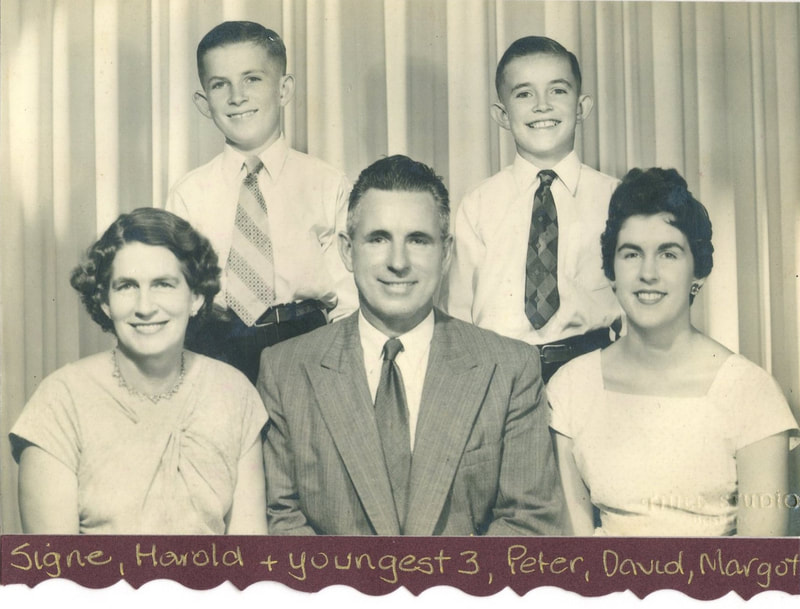

Harold was able to put a down payment on four blocks of land in the high north-west corner of St John’s Wood in preparation for his marriage to Signe Larsen on 22 October 1932. The two corner blocks for himself, totalling 48 perches, cost him £25.

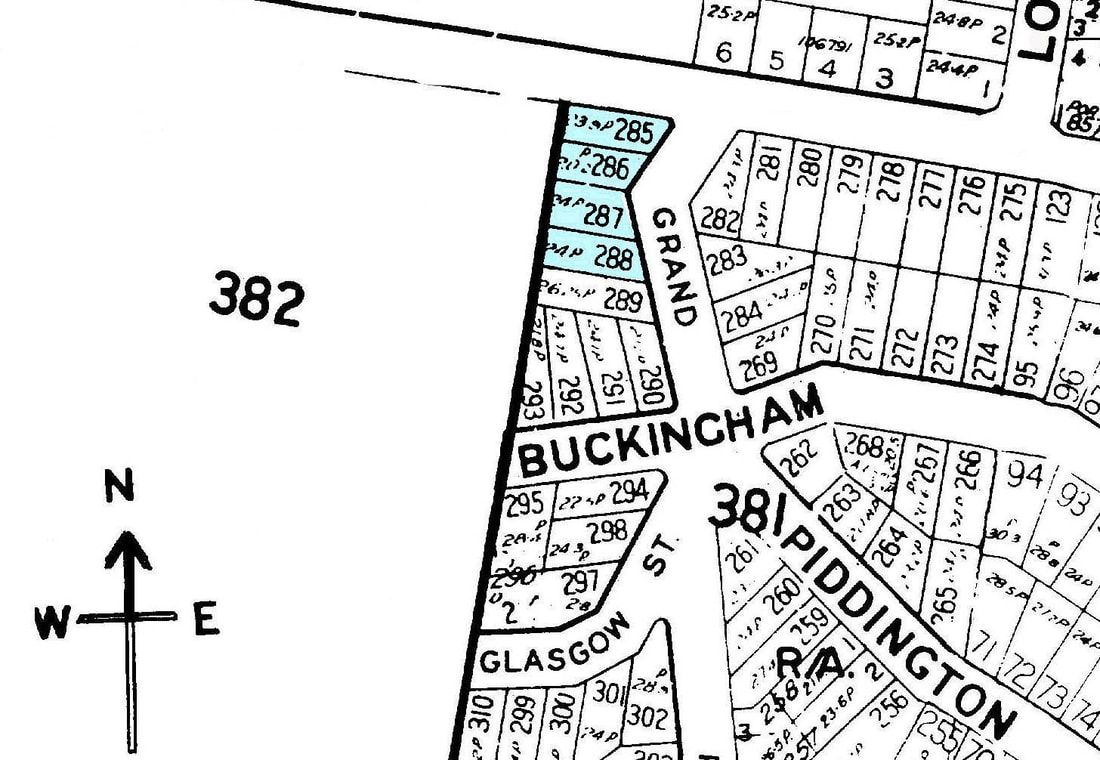

There was a flat area above a steep slope down to the road. Before the wedding, he pitched a tent on the land and they left all they owned in it while they went on their honeymoon. Unfortunately, a storm erupted in their absence, and blew the tent over and most of their belongings were lost. They had to return to Signe’s family home in Nundah to live while Harold purchased sheets of fibro and built a temporary home for them to commence their married life. It was into this dwelling, in the background of the photograph below, that they welcomed their first-born daughter, Kaye, in October, 1933. The group pictured includes top left Beth and Ed, front row from right, Signe and baby Kaye, toddler Vilma and her mother, Harold’s sister Dorrie. The shack later became his storage shed.

Their only vehicle was his Harley Davidson motorbike, onto the side of which he built a wooden box. The box was used to transport Signe and baby Kaye, and for work purposes to carry timber to build nearby houses. The timber, of course, was much longer than the bike, so it dragged along on the dirt roads of St Johns Wood to the site of the house he was building. He also used a push bike which he bought brand new for £5 with the profit he made on his first house.

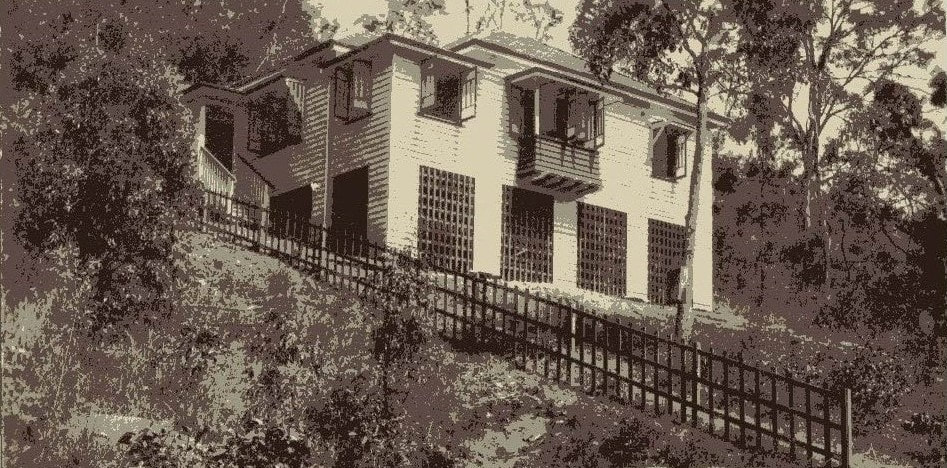

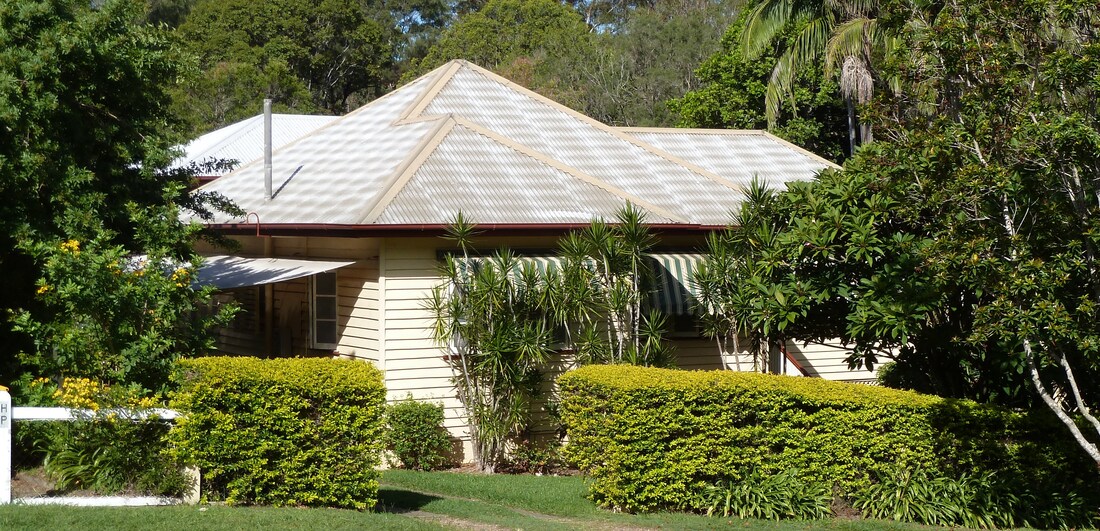

Harold acquired a bank loan to purchase the materials to build his own home. The land was granite so building foundations was challenging. They would drill four holes in the rock, insert four reinforcing rods and then pour cement into the stump hole. By the mid-1930s their home was finished at 52 Grand Parade, with the characteristic vertical and horizontal batons enclosing downstairs. Brother, Ed, worked for him for a time as his business manager from an office under the house. He called their home Frome after mother Ada’s birthplace.

Harold acquired a bank loan to purchase the materials to build his own home. The land was granite so building foundations was challenging. They would drill four holes in the rock, insert four reinforcing rods and then pour cement into the stump hole. By the mid-1930s their home was finished at 52 Grand Parade, with the characteristic vertical and horizontal batons enclosing downstairs. Brother, Ed, worked for him for a time as his business manager from an office under the house. He called their home Frome after mother Ada’s birthplace.

The original Hodges family home – 52 Grand Parade, St John’s Wood

During World War 2 Harold was unable to procure materials for building houses. The American army presence was strong and they were able to access building materials readily. There weren’t many cars privately owned in those days and the Americans took over ownership of his 1930s Chev utility similar to the one below.

During World War 2 Harold was unable to procure materials for building houses. The American army presence was strong and they were able to access building materials readily. There weren’t many cars privately owned in those days and the Americans took over ownership of his 1930s Chev utility similar to the one below.

He replaced it with a 1936 blue Morris 8 ute, similar to the one below, which he drove throughout the war. He added a side support to carry longer timber.

Harold agreed to work for the army in construction. One of his jobs was foreman for the building of huge timber storage sheds with fibro rooves near the airport. He knew and worked under General Macarthur during the war. He did the fit out for Macarthur Chambers on the corner of Queen and Edward Street. The war room remains as a museum to this day, but the felt sound sealing around the openings has deteriorated with time.

His three carpenters Freddie Sayers, Jack Christensen and Errol Klaus went to the war. And returned.

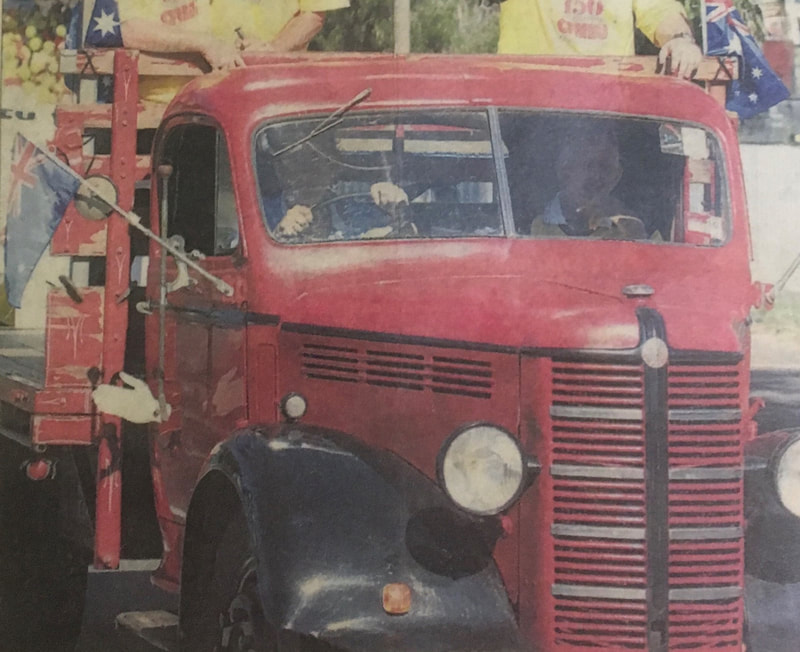

Post war, building materials were available again. He would have five houses on the go at one time. He allowed approximately twelve weeks to build a house. Once vehicle imports were flowing again after the war, he bought and drove a red British Bedford and drove it for years.

His three carpenters Freddie Sayers, Jack Christensen and Errol Klaus went to the war. And returned.

Post war, building materials were available again. He would have five houses on the go at one time. He allowed approximately twelve weeks to build a house. Once vehicle imports were flowing again after the war, he bought and drove a red British Bedford and drove it for years.

He built around sixteen houses in the Woods. How did he go about it?

He leased from the Council the space between the military boundary and his side fence. He built a road on it up to his house. After he measured up his requirements to build each new house, he’d place an order with Winn Brothers sawmill at Samsonvale.

The pile of timber would arrive on an old flat backed truck, a jinker. The timber was held together by a chain. The barefoot driver would jump out, climb up and release the chain and the load of wood would fall to the ground all around the truck in “a higgledy piggledy manner”. Son David recalls, as a small boy, the jinker standing up on its back wheels at times to tip off the timber, then dropping down again. As daughter Kaye recalls, “We used to dread it. We were the workforce “. Younger sister Margot says it was child labour.

All the timber had to be stacked that night. They each had their role. Margot had to pick up the small bits, and batons. Kaye, her share, and Geoff carried the big pieces with their father. Mother Signe would be looking out the window wondering when they would be able to come in for dinner.

He leased from the Council the space between the military boundary and his side fence. He built a road on it up to his house. After he measured up his requirements to build each new house, he’d place an order with Winn Brothers sawmill at Samsonvale.

The pile of timber would arrive on an old flat backed truck, a jinker. The timber was held together by a chain. The barefoot driver would jump out, climb up and release the chain and the load of wood would fall to the ground all around the truck in “a higgledy piggledy manner”. Son David recalls, as a small boy, the jinker standing up on its back wheels at times to tip off the timber, then dropping down again. As daughter Kaye recalls, “We used to dread it. We were the workforce “. Younger sister Margot says it was child labour.

All the timber had to be stacked that night. They each had their role. Margot had to pick up the small bits, and batons. Kaye, her share, and Geoff carried the big pieces with their father. Mother Signe would be looking out the window wondering when they would be able to come in for dinner.

A more fun memory of his children is that their father always had left over unusable timber, so they used to collect and stack it on the corner of Grand Parade and St John’s Avenue, then cover it with branches to make the stack each year for Guy Fawkes night.

People from everywhere would bring their crackers and sparklers and rockets and come to celebrate around a big bonfire. This was the start of a long local tradition.

This photo is of a bonfire in St Johns Wood in 1961. See the small children climbing on it, adding their contributions. Whether it was on this same site cannot be guaranteed, but the photo brings back happy memories for us all.

People from everywhere would bring their crackers and sparklers and rockets and come to celebrate around a big bonfire. This was the start of a long local tradition.

This photo is of a bonfire in St Johns Wood in 1961. See the small children climbing on it, adding their contributions. Whether it was on this same site cannot be guaranteed, but the photo brings back happy memories for us all.

|

In the late 1940s he was offered by government the chance to buy a Ford Deluxe ute. He chose to sell it on for more than he paid for it, which enabled him to buy a red Commer for work purposes plus a 1948 Humber Super Snipe, with registration number plate Q473973, pale green in colour. This was their first family car. He later painted it white, then black. By now, he and Signe had five children, and they were a prospering two-vehicle family.

|

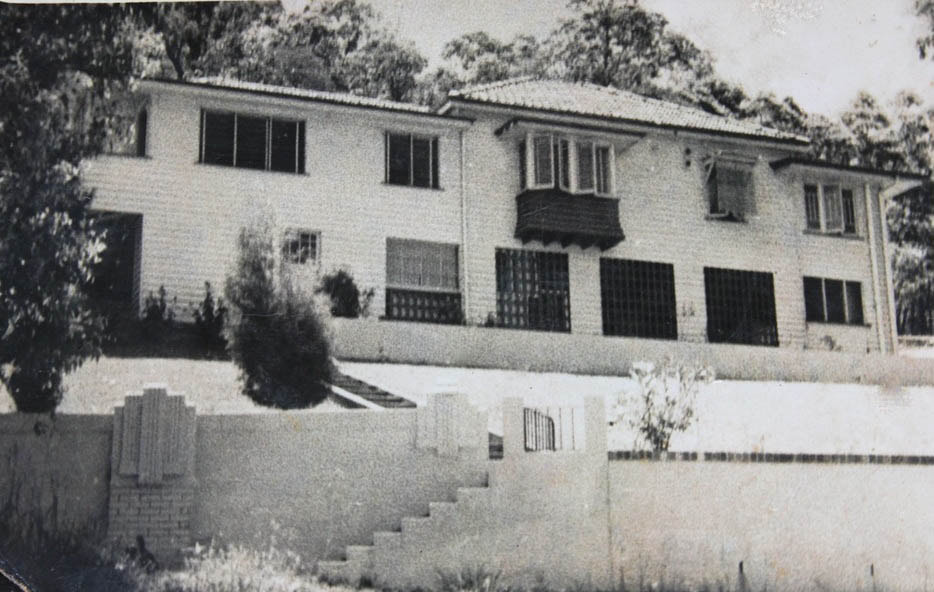

The completed Bayley home- 42 Grande Parade.

The completed Bayley home- 42 Grande Parade.

There were three main employers of builders in those early days, the housing commission, war service and private architects. Harold worked for all three before taking the risk of spec building. In the event, all his spec houses sold and people would come knocking on his door, asking him to build their house. He didn’t end up building the Bayley home for his sister Dorothy and husband Brian because he was underquoted! But he helped later with additions and it is still standing in 2019.

Harold employed carpenters, labourers, brick layers, roof tilers and painters - all trades except plumbers. He did a lot of extensions and renovations in addition to full houses, including extensions to the southern side on his own home, 52 Grand Parade, as below.

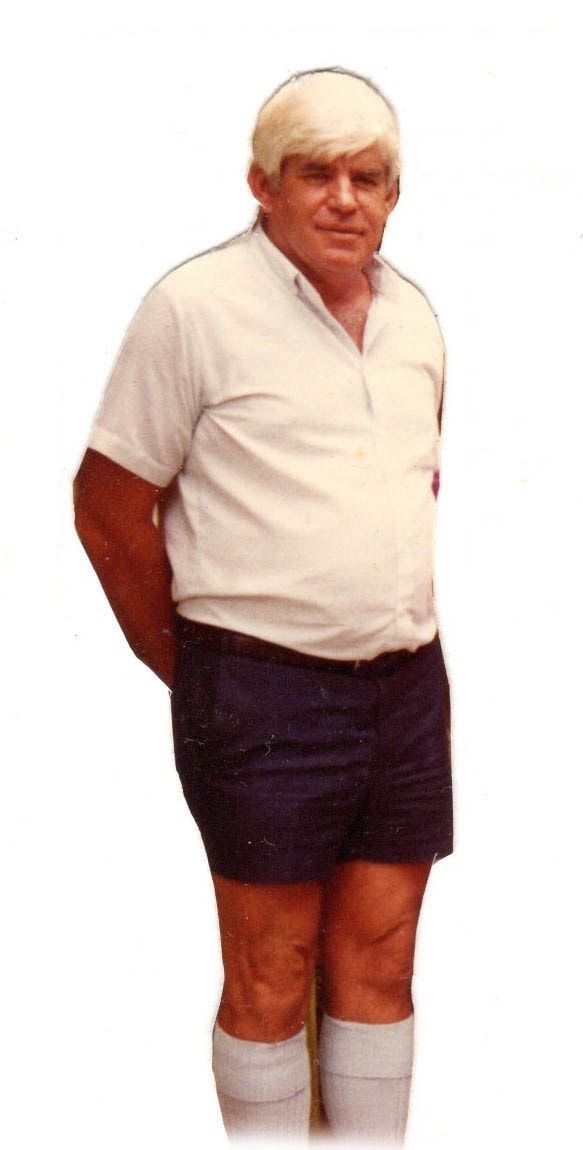

He treated his apprentices well. He was generous with them, less so with his son, Geoff. He ruled a tight ship at home but was generous with Christmas occasions, holidays, drives, weekend picnics and the latest appliances for their home. Harold read a lot. He was good to people and he was popular as a builder. He was fit and joined the YMCA. Kaye recalls he had a skipping rope at home and he skipped with this even after a day at work. He was interested in healthy food and provided well for it. He ate wheat germ when most didn’t bother. The children were not allowed soft drink as he said it would rot their insides.

In the late 1940s he gave a quote of £15,000 and won the tender to build St Pauls Anglican brick church on the corner of Waterworks Road and Jubilee Terrace.

There was a lot of work done on the church largely by supervised volunteers. The red face bricks were brought down from Wide Bay but there was a shortage of common bricks. As son David says, “nothing stopped Dad”. Harold had a brick making machine made and set it up on the Jubilee Terrace footpath where hundreds of concrete bricks were produced. There were no pallets in those days and the kids were expected to carry the bricks from where they were made on the footpath over to the church.

The foundation stone was set and blessed on 1 July 1951 and the church opened the following year.

How did he build those lovely wooden arches of the ceiling? He spread out paper on the floor of the old church hall and drew out the curves freehand, then took the drawings to Brett’s hardware to cut the timber to shape. Geoff recalls helping his father lift the arches up with ropes by hand. And so it unfolded. The Lych gate is now heritage listed.

At the front of the church is a columbarium in which Harold’s ashes lie, along with those of his brother Ed.

In the late 1940s he gave a quote of £15,000 and won the tender to build St Pauls Anglican brick church on the corner of Waterworks Road and Jubilee Terrace.

There was a lot of work done on the church largely by supervised volunteers. The red face bricks were brought down from Wide Bay but there was a shortage of common bricks. As son David says, “nothing stopped Dad”. Harold had a brick making machine made and set it up on the Jubilee Terrace footpath where hundreds of concrete bricks were produced. There were no pallets in those days and the kids were expected to carry the bricks from where they were made on the footpath over to the church.

The foundation stone was set and blessed on 1 July 1951 and the church opened the following year.

How did he build those lovely wooden arches of the ceiling? He spread out paper on the floor of the old church hall and drew out the curves freehand, then took the drawings to Brett’s hardware to cut the timber to shape. Geoff recalls helping his father lift the arches up with ropes by hand. And so it unfolded. The Lych gate is now heritage listed.

At the front of the church is a columbarium in which Harold’s ashes lie, along with those of his brother Ed.

The first spec house he built was 123 Royal Parade, followed by the one next door, number 3 Grand Parade, then on the corner of Grand Parade.

They still stand as of mid-2019 and have the distinctive Hodges features. As Margot says, “Dad was different”. He was creative with his designs, on the lookout for something different. He upheld a high standard for himself as a builder. He installed a composting toilet in the corner house. The Hodges family moved there from 52 Grand Parade around 1950. This became their custom. The family would move in to the just-built house while he was building the next one. In this instance, the next was what the family called “the pink house”, at 57 St John’s Avenue. They moved there in approximately 1952. This was a favourite of his wife Signe.

To quote his son Geoff, “Dad built houses where no one else would build them in that era.” The site where he built the pink house was steep, running down to the creek. There was no flat area at the top to place the house. People living opposite, like the Burdetts, were told their view would never be built out. That advice underestimated Harold’s willingness to forge new possibilities in building.

In this house Harold decided to implement all his best ideas and many are still evident in the house today – a brick fire place, built in wardrobes, a wide full width deep verandah at the back facing north and overlooking the creek paved with Italian terracotta tiles, wide double French doors leading out. The locks and handles were the best available. He designed a septic system to manage waste and the product was drinkable water. A Hills Hoist clothesline was erected on the steep slope and stands to this day. He placed the garage inside the house at the front. This was a very modern concept at the time.

When current owner, Margaret and family purchased the home nearly 30 years later in 1979, it was regarded as ultra-modern at that time. She and her family loved it at first sight. She very kindly allowed me to bring Geoff, Kaye and Margot to re-visit this lovely home after all these decades. Geoff and two other apprentices, Wally and Peter basically built it under his father’s instruction. Geoff says he was paid around 35 shillings a week when he was an early apprentice.

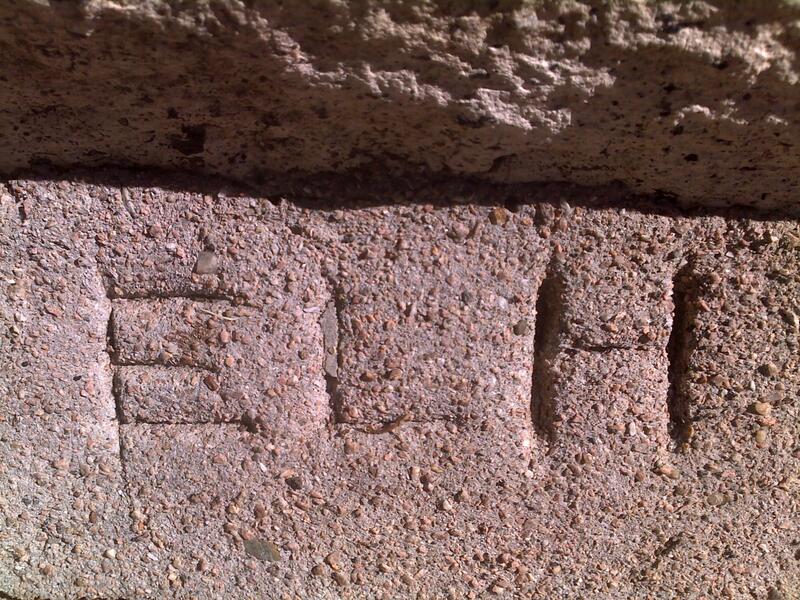

By the mid to late 1940s Harry had built 82 St John’s Avenue, opposite his own home, for his brother Ed and wife Beth, after initially accommodating them in a fibro cottage behind his own home. Ed was a fun character and to this day his initials carved in the cement of the front stairs can still be seen, standing for Edgar Leslie Hodges.

In this house Harold decided to implement all his best ideas and many are still evident in the house today – a brick fire place, built in wardrobes, a wide full width deep verandah at the back facing north and overlooking the creek paved with Italian terracotta tiles, wide double French doors leading out. The locks and handles were the best available. He designed a septic system to manage waste and the product was drinkable water. A Hills Hoist clothesline was erected on the steep slope and stands to this day. He placed the garage inside the house at the front. This was a very modern concept at the time.

When current owner, Margaret and family purchased the home nearly 30 years later in 1979, it was regarded as ultra-modern at that time. She and her family loved it at first sight. She very kindly allowed me to bring Geoff, Kaye and Margot to re-visit this lovely home after all these decades. Geoff and two other apprentices, Wally and Peter basically built it under his father’s instruction. Geoff says he was paid around 35 shillings a week when he was an early apprentice.

By the mid to late 1940s Harry had built 82 St John’s Avenue, opposite his own home, for his brother Ed and wife Beth, after initially accommodating them in a fibro cottage behind his own home. Ed was a fun character and to this day his initials carved in the cement of the front stairs can still be seen, standing for Edgar Leslie Hodges.

In 1941 he bought land in Gresham Street where he later built number 23 as a spec house. It was purchased by Signe’s brother, John Larsen and his wife Jean. Harold had plastered the main rooms, put batons underneath and weatherboards down to the ground with little stumps. Made it look a bit fancy. It’s where John and Jean raised their family of boys, Bob, Alan and Jim. There was a later extension which included the garage and room above it. The house was removed to another location in 2019.

He built number 21 Gresham Street, next door on the lower side. It was lived in until 2017, for a time as flats, before it was raised to make it a two-storey house.

He built a house in Laird Street, opposite the Granite House, and two in Buckingham Street. As yet, I have been unable to identify these. Son Peter recalls him building early Mater Prize homes and he built a lot of housing commission houses in Holland Park. He used to lament having to travel so far and being required to build them all the same. He couldn’t help himself. He’d introduce small features where he could to give them a bit of individuality.

He built the home next door to his own, number 48 Grand Parade for Signe’s friend, Doris King, and husband Bert to whom he sold the land. He employed Bert for a time. The Kings lived out their lives in number 48, lifelong friends to his sister Dorrie, next door at 42.

He built the home next door to his own, number 48 Grand Parade for Signe’s friend, Doris King, and husband Bert to whom he sold the land. He employed Bert for a time. The Kings lived out their lives in number 48, lifelong friends to his sister Dorrie, next door at 42.

In the fifties and early 60s he built numbers 55, 59 and 61 St John’s Avenue on the slope adjacent to the pink house. A good image was not obtainable for 55.

Current local aboriginal elder Nurdon Serico, classmate at Ashgrove school of Harold’s daughter Kaye, recalls of Harold, “I could appreciate his work. He built a lot of those high-quality houses, for example, in Mareeba Road in Ashgrove. You could tell the houses he built. They often had an oriel window, sometimes called a porthole.

Since 1924, Wilfred and Bessie Heyes had owned the 4 ½ acres bounded by Firhill Street, Baileys Road and Waterworks Road, just outside the boundaries of St John’s Wood. They ran a poultry farm on it as well as a few cows, and fruit trees and vegetables. In 1948 they sold it to “developer”, Harold Hodges.

He subdivided it with the aid of surveyor and friend Clem Jones and built the next family home in the early 1950s at 618 Waterworks Road on the corner of Firhill Street. Son Peter described this home as a palace and it was his brother David’s favourite. It was two storeys at the back and there was a bedroom for each of the children. The fireplace had an ash pit underneath, so no one had to carry the ash to the outside.

But they weren’t there for long. Harold sold it to an eager country buyer and they had to vacate in a hurry, so he built their next home across the adjacent paddock at 23 Baileys Road in two weeks. They didn’t have far to transport their possessions across to their next home.

David recalls living in nine houses by the time he was nine. When we tried to account for them all, we counted eight. They were a builder’s family and always on the move.

Since 1924, Wilfred and Bessie Heyes had owned the 4 ½ acres bounded by Firhill Street, Baileys Road and Waterworks Road, just outside the boundaries of St John’s Wood. They ran a poultry farm on it as well as a few cows, and fruit trees and vegetables. In 1948 they sold it to “developer”, Harold Hodges.

He subdivided it with the aid of surveyor and friend Clem Jones and built the next family home in the early 1950s at 618 Waterworks Road on the corner of Firhill Street. Son Peter described this home as a palace and it was his brother David’s favourite. It was two storeys at the back and there was a bedroom for each of the children. The fireplace had an ash pit underneath, so no one had to carry the ash to the outside.

But they weren’t there for long. Harold sold it to an eager country buyer and they had to vacate in a hurry, so he built their next home across the adjacent paddock at 23 Baileys Road in two weeks. They didn’t have far to transport their possessions across to their next home.

David recalls living in nine houses by the time he was nine. When we tried to account for them all, we counted eight. They were a builder’s family and always on the move.

Harry also built the row of houses along from 618, just basic houses to recoup some outlays. They remain as of 2019.

He donated the area behind that row of houses to the Anglican Church. It was later purchased by the Baptist Church which occupies it to this day. 618 was demolished around 2017 because of extensive rot owing to the small watercourse that ran near it. It was replaced by a car park for the church.

After living in Baileys Road, Harold purchased land and built a two-storey block of units at 525A Coronation Drive. Youngest son David recalls carrying a brick at a time from the footpath to the building area as his siblings before him had, lamenting the chafing of his forearms from the task. They lived there on the top floor while the younger boys finished their education at Churchie. The kids recall saying to each other “we’re going to a posh place now.”

Harold’s original home at 52 Grand Parade has since been rebuilt in the 1990s but an original bedroom with ornate plaster ceiling was retained. With the more recent renovations, there’s a subtle unplanned tribute to Harold on the front wall.

In the mornings, when the rising sun casts its light on the two black vertical light shades, a shadow is cast which has the appearance of HH for Harold Hodges.

He donated the area behind that row of houses to the Anglican Church. It was later purchased by the Baptist Church which occupies it to this day. 618 was demolished around 2017 because of extensive rot owing to the small watercourse that ran near it. It was replaced by a car park for the church.

After living in Baileys Road, Harold purchased land and built a two-storey block of units at 525A Coronation Drive. Youngest son David recalls carrying a brick at a time from the footpath to the building area as his siblings before him had, lamenting the chafing of his forearms from the task. They lived there on the top floor while the younger boys finished their education at Churchie. The kids recall saying to each other “we’re going to a posh place now.”

Harold’s original home at 52 Grand Parade has since been rebuilt in the 1990s but an original bedroom with ornate plaster ceiling was retained. With the more recent renovations, there’s a subtle unplanned tribute to Harold on the front wall.

In the mornings, when the rising sun casts its light on the two black vertical light shades, a shadow is cast which has the appearance of HH for Harold Hodges.

Written by his niece Sandra Bayley - August 2019, with the assistance of her cousins Kaye, Geoff, Margot, Peter and David, Harold’s children.

I have an enormous sense of gratitude that St John’s Wood has been my life long home, as have my parents and siblings We owe this good fortune entirely to Uncle Harold. It was he who found this lovely place in the 1930s and urged my parents to buy a block of land on the hill and build their home. My mother lived here until she was 100. Sandra Bayley

I have an enormous sense of gratitude that St John’s Wood has been my life long home, as have my parents and siblings We owe this good fortune entirely to Uncle Harold. It was he who found this lovely place in the 1930s and urged my parents to buy a block of land on the hill and build their home. My mother lived here until she was 100. Sandra Bayley

| harry_hodges__3_.pdf | |

| File Size: | 5084 kb |

| File Type: | |